Using a newly developed, 3-D chamber, a researcher at the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center is testing living cancer tumors to learn how patients will respond to immunotherapy treatment.

Mass General Cancer Center brings together the most visionary minds in medicine to generate bold breakthroughs in cancer care.

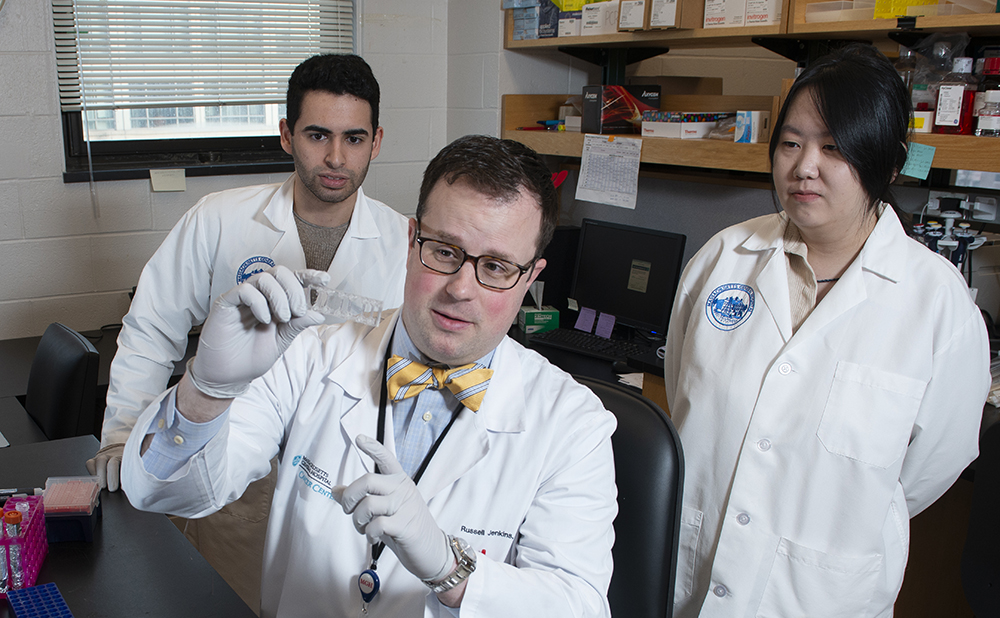

Medical oncologist Russell Jenkins, MD, PhD, and colleagues have developed a trailblazing, 3-D technique to help solve one of the most challenging problems of modern cancer therapeutics. They are working to determine, in advance, which drug will successfully treat an individual patient’s cancer.

Inspired during his medical training by the death of his uncle — a globe-trotting humanitarian, firefighter and nurse — Dr. Jenkins decided he wanted to bring his love of science directly to patients. “It’s about translating what I learn in the lab to patients and translating what I learn from patients back to the lab to create a cycle between the two,” Dr. Jenkins says.

That vision exemplifies the long-standing tradition of physician-scientists at Mass General Cancer Center, says Keith Flaherty, MD, the center’s director of clinical research. “Russ is able to see the human relevance of his laboratory work and adjust his scientific strategy in parallel with that,” Dr. Flaherty says. Mass General Cancer Center brings together the most visionary minds in medicine to work simultaneously with patients and scientists to generate bold breakthroughs in cancer care.

New Test for Immunotherapy Treatment

“We don’t really have a good way of predicting which patients our immunotherapy drugs are going to work for,” Dr. Jenkins says. The new 3-D technology, which he is testing in the laboratory on patient tumors, may ultimately help determine if a patient will benefit from immunotherapy treatment. In this way, patients who won’t benefit can avoid the risk of serious side effects of immunotherapy.

Currently, Dr. Jenkins is working with tissue samples from patients with advanced melanoma because their tumors are large and contain enough cancer cells and immune system cells. He places the sample in a tiny, microfluidic chamber recently developed at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Microfluidics is a new technology in which liquids are directed through a series of tiny channels.

Once in the chamber, the patient’s cancer cells and immune cells multiply together to form a three-dimensional sphere. Then, a liquid immunotherapy drug known as a PD-1 inhibitor is channeled around the sphere on all sides. The 3-D method mimics real-life conditions in the human body and allows physicians to observe, in real time, whether the drug is spurring the immune cells to attack the cancer.

“It’s a very dynamic process,” Dr. Jenkins says. “The tumor cells are alive, and the immune cells are alive, and we can observe them interacting.”

Philanthropic support can help accelerate the process because many more tissue samples need to be tested.

Breaking the Log Jam

Once fully developed, the technique could be used in patients in earlier stages of cancer. It may even be useful for testing many other cancer drugs.

That’s important, Dr. Flaherty says, because cancer-drug testing has hit a plateau in recent years. Many therapies which looked promising in the laboratory were not successful when tested in clinical trials in humans, he says. This new method may help break the log jam.

“This platform, which Russ and a few other investigators have developed, could be used to vet different therapies and decide which ones to prioritize,” Dr. Flaherty says.

Inspired by a Childhood Hero

For Dr. Jenkins, the memory of his childhood hero serves as a compass, linking his laboratory science with patient care. His uncle, who spent his life serving others around the globe, was diagnosed with cancer while Dr. Jenkins was still a medical student.

Returning to the United States for treatment, he kept in touch with his nephew during his long and involved treatment for acute myeloid leukemia. Even as he approached death, he encouraged Dr. Jenkins’ research and urged him keep pursuing his goals.

“Russ, stay encouraged about what you are doing,” his uncle wrote. “ I mean it, there are answers for this stuff and your efforts will always be important.”

The experience altered the direction of Dr. Jenkins’ career toward the kind of translational research he is doing today.

“I knew then that my true north would be to bring discoveries from the bench to the bedside,” he says. “I wanted my laboratory to focus on research that would advance treatment for my patients.”

For more information about 3-D microfluidic cancer research or to make a donation, please contact us.