This story was originally published in April 2014 and updated in October 2020.

Regaining independence for people who are paralyzed is an ambitious goal, admits Leigh Hochberg, MD, PhD, a critical care neurologist and director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Neurotechnology and Neurorecovery. Yet Dr. Hochberg is optimistic about the potential of an investigational technology called BrainGate to restore mobility and communication for patients unable to move or speak.

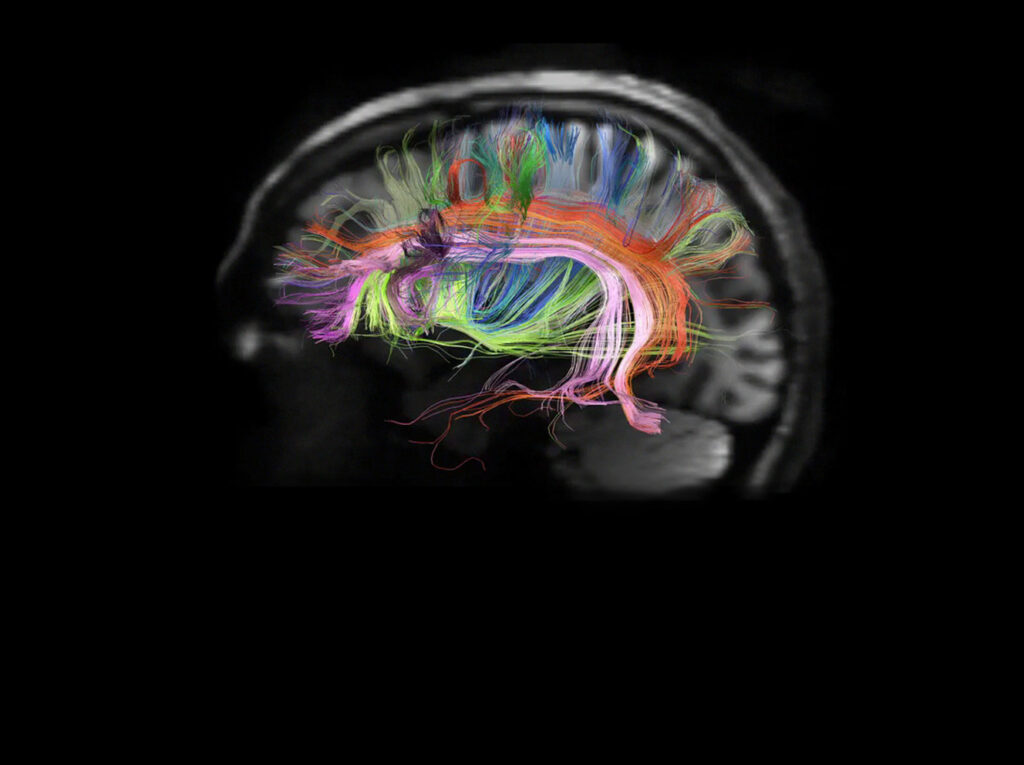

Led by Dr. Hochberg, this multi-institutional research effort, including partners at Brown University, Case Western Reserve University, Stanford University and the Department of Veterans Affairs, aims to reconnect the brain to limbs. In the BrainGate system, a baby aspirin-sized sensor covered with tiny electrodes is surgically implanted in the patient’s motor cortex, a part of the brain that controls movement. The sensor records the brain activity generated by the intention to move. A computer program then decodes this data into commands that direct the movement of assistive devices such as a robot arm or hand. In previous trials, people with paralysis have demonstrated success by controlling a computer cursor just by thinking about moving their own hand.

A Robot Arm and a Joyful Moment

In 2011 clinical trials, Cathy Hutchinson, who was paralyzed by stroke 15 years earlier, was able to control a robot arm just by thinking about moving her own hand. For the first time since her stroke, she was able to pick up a bottle containing coffee and drink it without any assistance. The joy on her face from taking that drink using the robot arm was unforgettable, Dr. Hochberg says. Ms. Hutchinson died in October 2020.

“We want BrainGate to work wherever the user is, not just in a carefully controlled laboratory environment.”

More funding will help the team discover better ways to decode brain signals for controlling assistive devices. Another goal is to develop a wireless and fully implantable device that can be turned on by the user at home 24 hours a day. Dr. Hochberg compares today’s system to early heart pacemakers, which were pushed around on a cart. The current device, limited to BrainGate participants, can only be turned on by a research team member.*

Applying the Concepts to Other Diseases

“We test the device in the patient’s residence — in their living room. We want BrainGate to work wherever the user is, not just in a carefully controlled laboratory environment,” Dr. Hochberg explains. “It is a privilege to work with the participants in our research. They allow us in their homes twice per week for a year or more and provide critical feedback to make the system even better.”

Fourteen patients have been enrolled in the trials to test safety and feasibility. Dr. Hochberg credits Mass General and the Neurology Department for its extraordinary environment and infrastructure for cutting-edge clinical and translational research. “Together with [Mass General neurologist] Syd Cash, we’re also taking what we’re learning about the brain with this sensor to help patients with epilepsy,” he says. “We hope to someday better understand seizures and to predict when they will happen.”

The potential impact of this work is far reaching. Every year, millions of patients suffer strokes, spinal cord injuries and neuromuscular diseases. “The BrainGate trial was one of the best experiences I’ve ever had,” emailed Cathy. “It gave me hope, because it gave me a goal to reach for.”

To learn more about how you can support neurological research, contact us. You can also support the BrainGate project by making a donation here.

*Caution: Investigational device. Limited by federal law to investigational use.