Alister Martin, MD, MPP, learned early in life that people do not only go to the emergency department (ED) for medical emergencies — they also go there for food, shelter, warmth, protection and doctor’s notes for time missed at work.

“Growing up in a working-class community in New Jersey and being raised by a working, single mother, I learned that the emergency department played an outsized role in the lives of low-income and marginalized patients,” says Dr. Martin.

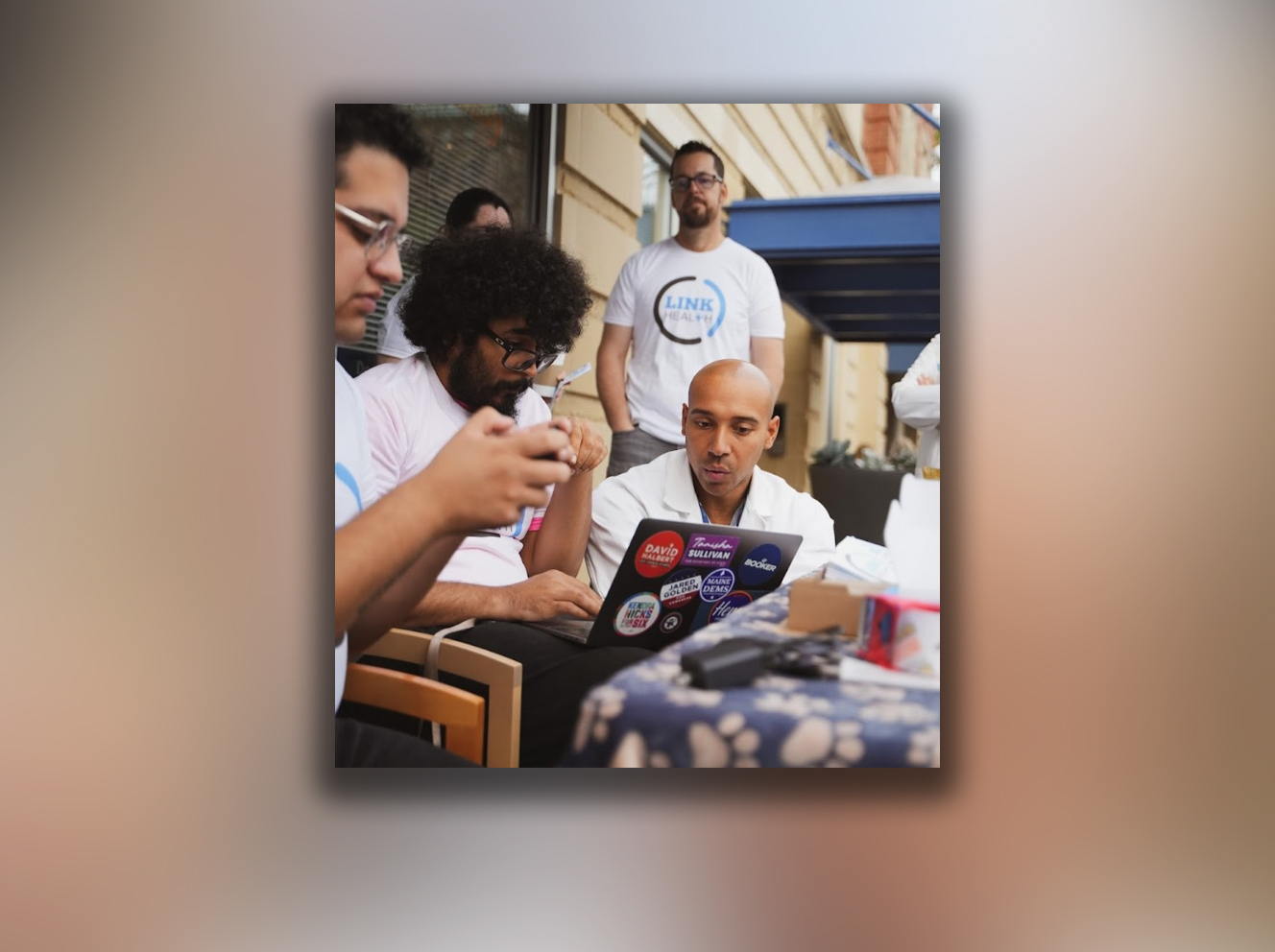

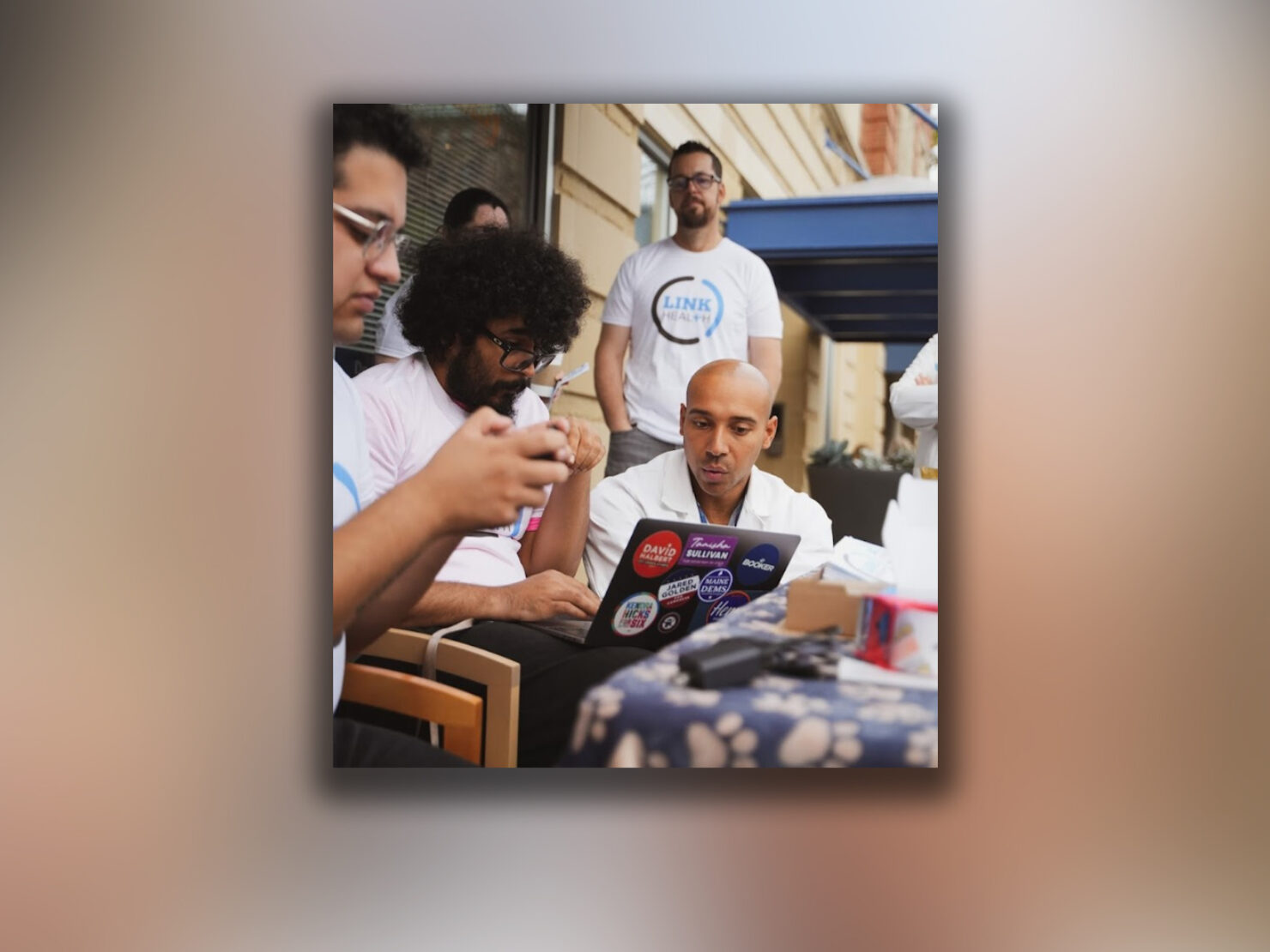

This realization was the initial catalyst that led him to become an emergency medicine physician. And later, to found Link Health, an organization that leverages the time patients spend in waiting rooms at health centers and emergency departments and connects them with federal benefit programs that offset healthcare and energy costs, provide nutrition support and more.

Here is how Link Health works: The organization’s participating community health workers, who work in the ED or at participating community health centers, screen patients who are on Medicaid to determine whether they have a “digital equity gap, the disparity in folks’ ability to access the internet and technology caused by socioeconomic status”— or other health related social needs. If a patient screens positive, meaning they are unable to readily access the internet, the Link Health team enrolls them over the phone in a federal program called Lifeline. Lifeline assists with the cost of phone or internet service or one of seven other benefit programs, to help with things ranging from childcare subsidies to utilities assistance.

To date, Link Health’s team of certified patient navigators have helped distribute more than $2.7 million to low-income families by connecting them with benefits they are entitled to as patients who qualify for Medicaid.

Connecting the Dots

As a medical student in the emergency department, Dr. Martin regularly encountered people who had sought help with nonemergent matters, and he quickly learned that the ED did not always have the resources needed to help these patients.

Having witnessed how, as he puts it, “ill-equipped” the healthcare system was to address health issues related to socioeconomic status, Dr. Martin says he pursued a master’s degree in public policy at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. During that time, Dr. Martin says he began to grasp how to “pull the levers of change.”

After earning his degree, he went on to serve as a 2021-2022 White House Fellow in the Office of Vice President Kamala Harris and the West Wing Office of Public Engagement, where he says he continued to learn how to alleviate issues facing patients due to difficulty accessing resources.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Martin worked as an emergency medicine physician at Massachusetts General Hospital. He says that during that time, he began to notice that the majority of the patients requiring intubation were Black and Brown, despite those demographics making up the minority of all patients treated at Mass General.

He says he will never forget one patient, an older Latino man, who he treated for complications of COVID-19. When Dr. Martin asked whether he was vaccinated, the older man asked in reply, “How do I do that?” Dr. Martin explained he would need to go online to schedule an appointment, which opened up a conversation about the patient’s ability to access the internet. This encounter got Dr. Martin thinking about the larger issue of access to technology and resources, and the ways this could be addressed in the emergency department.

“I started thinking about how many other patients didn’t have access to a smartphone or computer,” Dr. Martin says. “And how they essentially had been told to do something by the government — to get vaccinated — and that was not possible for them.”

Building Resources

Eighty percent of patients on Medicaid insurance live on $20,000 or less per year. “That level of poverty does two things — it increases the likelihood that those patients will be living with dangerous, chronic, comorbid conditions,” Dr. Martin says. “It also puts strain on the healthcare system to treat a much sicker and much more resource-constrained population — with some estimates putting the spending required to address this ‘health-wealth gap’ at more than $320 billion annually.”

Dr. Martin says that Link Health is working to address this gap by connecting patients with resources they qualify for, starting with programs like Lifeline, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) and Transitional Aid to Families with Dependent Children (TAFDC). These connections link patients with critical resources that help meet their basic needs.

Similar to Vot-ER, another program Dr. Martin founded to help patients register to vote while at the emergency department, Link Health began at Mass General, and has since expanded to other hospital networks and states. However, in order to continue expanding this successful pilot program and connect more patients with internet access and to the broad range of other federal assistance programs available to them, Dr. Martin and his team require philanthropic investment for operational costs and staffing.

“A $100,000 gift to support this work could help us connect patients to more than $2 million in existing federal funding,” Dr. Martin says. “Getting patients enrolled and getting those resources into their hands is the tricky part, and that’s what we’re making possible with Link Health.”

To support Link Health at Mass General, click here.