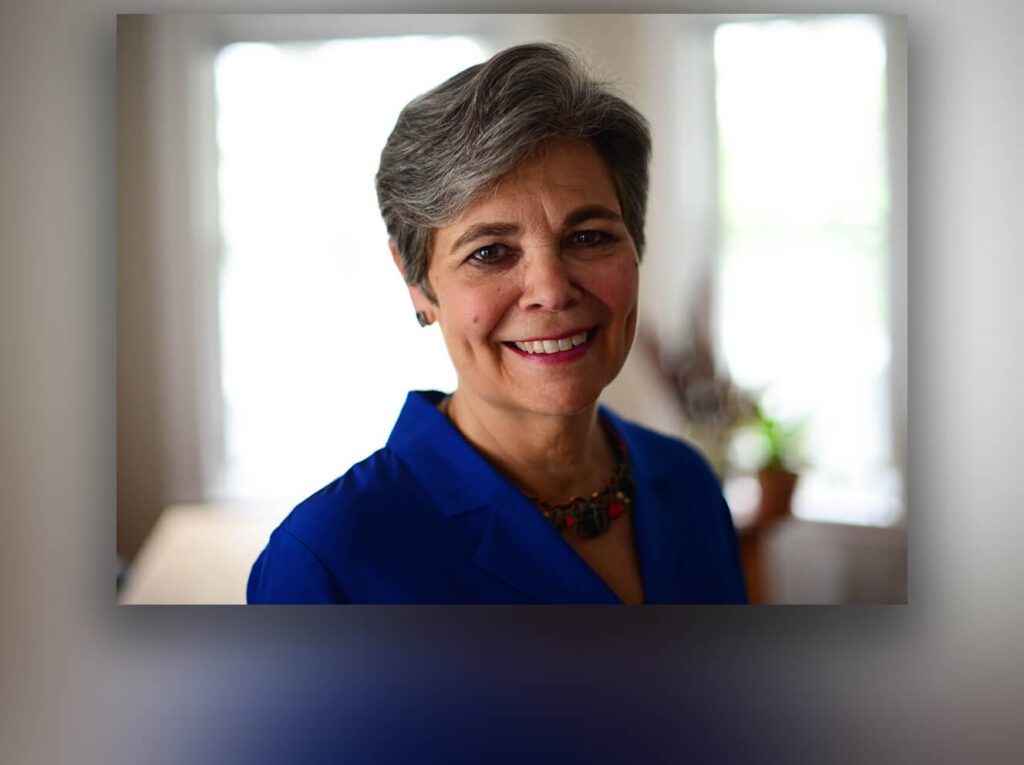

Kamryn Eddy, PhD, is co-director of the Eating Disorders Clinical and Research Program at Massachusetts General Hospital. She is also an associate professor of Psychiatry at the Harvard Medical School. Dr. Eddy specializes in assessing and treating children, adolescents and young adults with eating disorders.

What led you to care for people with eating disorders?

I had a close friend in high school diagnosed with anorexia. Nobody knew what to say to her. When I approached her about it, I got a window into what it was like for her — lonely and painful. By the time I met her, she had been struggling with it for several years. Doctors had told her because of her eating disorder, she had brittle bones and would never be able to have children.

I remember thinking, at 16, ‘How could somebody say that to her, make a dire prediction about the rest of her life?’

We lost touch. I pursued a career in psychology and began conducting research on eating disorders. Ten years ago, I reconnected with my friend and learned it took her until her 30s to recover. She had a child of her own and enjoyed being a mother and her career. My friend’s story seems to match what my research team found: Recovery is possible, it just takes time.

Who is affected by eating disorders?

Anorexia and bulimia, two common eating disorders, begin most often during the teenage years, with peak onsets at ages 14 and 17. They can also reoccur or start at any point in life. Triggers include transitions like puberty, going to college, moving or menopause. Anorexia and bulimia affect women more than men, but many men do have eating disorders and rates of binge eating disorder and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder are similar between women and men.

What were the results of your recent research?

By 22 years, two-thirds of the women with anorexia got better. Recovery was slower, but likely for most women.

It was often thought eating disorders, especially anorexia, were a lifelong struggle. Our research points to a more hopeful future for people with the condition.

In our study of 246 women with anorexia and bulimia, we found that by the first decade of follow-up, two-thirds of women with bulimia got better, while only one-third of women with anorexia recovered. However, by 22 years, two-thirds of the women with anorexia got better. In other words, recovery from anorexia was slower, but it was likely for most women.

The new research shows recovery is possible when considered over a longer time frame.

What does recovery look like?

We consider a patient recovered when they do not have behaviors associated with these disorders, such as restricting calories as in the case of anorexia, or bingeing and purging after eating as in the case of bulimia. But equally important, we also want patients to feel better about their bodies. Their weight and shape should not be the most important aspect of how they judge their self anymore.

What type of treatment is available at Mass General?

Most patients receive outpatient treatment in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy, a form of talk therapy which allows patients to work with a therapist to change negative thinking patterns. For younger patients, the therapy is family-based.

There are no medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat anorexia, but there are some medications for bulimia and binge eating disorder. Patients are invited to participate in research and partner with us in trying to better understand these illnesses. One of the reasons we originally did the study in the 1980s was patients would ask us, “Will I get better and what can I expect over time?” And we didn’t have that data. Now, we do.

What does the future of eating disorder research look like?

These are brain-based illnesses. No single gene has been identified, but these disorders do run in families, so there is clearly a genetic vulnerability to traits such as anxiety or perfectionism that can increase the risk for eating disorders. My team is conducting functional magnetic resonance imaging research with adolescents who have a spectrum of eating disorders. We want to study the brain during this time of rapid brain development and hormonal changes. We are following these patients for two years, during which time we expect most to improve and many to fully recover.

We need to get people better quicker and philanthropy could help.

How can philanthropy help?

Our clinical team at Mass General is small. Adding another psychiatrist or a clinical psychologist would make a big difference. Establishing a postdoctoral fellowship could help us train more clinicians and investigators. Philanthropy could expand our adolescent research by allowing us to follow patients longer in our neuroimaging studies to learn how to help patients who are slow to recover. I believe it’s positive that two-thirds of people get better over time, but 20 years is a long time to be ill. We need to get people better quicker and philanthropy could help.

To make a donation to support the work of Dr. Eddy and her colleagues in the Eating Disorders Clinical and Research Program please contact us.