The FDA’s approval of lecanemab in January 2023 was a historic moment in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease. After decades of setbacks, caregivers finally have a drug — lecanemab, marketed as Leqembi® — proven to slow the cognitive decline associated with the disease. While lecanemab is far from a silver bullet — the drug’s effects are modest and only in patients in the early stages of the disease — it’s approval marks important step forward.

“Lecanemab shows we can effectively change the disease biology, and that’s something the field can build on,” says Merit Cudkowicz, MD, MSc, chair of neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital and director of the Sean M. Healey & AMG Center for ALS. “But to meet the urgent needs of patients and families, we need to do more than just slow decline. We need to be able to prevent, stop and even reverse Alzheimer’s, and that will demand an array of innovative, personalized options for prevention, diagnosis and treatment.”

With that in mind, researchers and clinicians across Mass General are developing new strategies for Alzheimer’s to improve outcomes for many at risk of the disease and those affected.

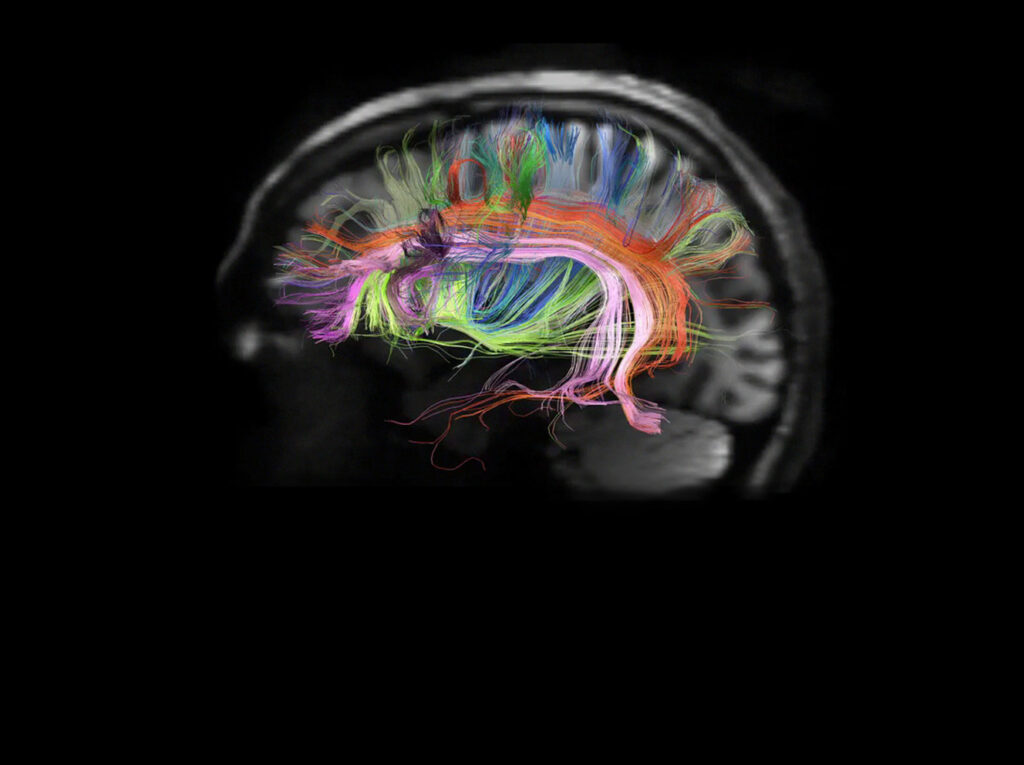

Prioritizing Early Detection

One of the challenges of Alzheimer’s disease is that it typically isn’t diagnosed until the brain has deteriorated significantly — too late for lecanemab to be effective. To harness the drug’s benefits, early detection is imperative. Teresa Gomez-Isla, MD, PhD, chair of the Neurology Department’s Memory Division and the Anne B. Young, MD, PhD Endowed Chair in Neurodegenerative Disease, recognized this importance. Shortly after the approval of lecanemab, she partnered with colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital to launch the Alzheimer Therapeutic Program — an initiative designed to make it easier for Mass General Brigham patients to find out if they are good candidates for the drug and to ensure any side effects are addressed promptly.

“Early detection is critical to reducing the toll this disease takes,” says Dr. Gomez-Isla. “We are using our data to identify people at risk and develop improved therapies to preserve cognition for everyone.”

Finding New Hope in Old Therapies

Translating a lab discovery into a new patient-ready therapy is an arduous process, usually taking a decade or more. But Rudolph Tanzi, PhD, director of the McCance Center for Brain Health, is pursuing a different approach that has potential to shorten the drug development timeline for patients with Alzheimer’s.

In 2014, Dr. Tanzi and his team developed a human brain organoid model that allowed researchers to play out 30 years of Alzheimer’s development in six weeks. That model became the basis for the McCance Center’s Alzheimer’s Disease Clinical Trial Initiative — a broadscale effort to rapidly test and observe the impact of drugs on Alzheimer’s pathology.

“It’s made drug discovery 100 times faster, 100 times cheaper,” says Dr. Tanzi.

With this astonishingly efficient tool, his team has screened more than 1,700 drugs approved by the FDA for other uses and other natural products. More than 250 showed potential to slow or stop Alzheimer’s disease in the model. Dr. Tanzi is now planning human clinical trials to test those drugs in combination — an approach used successfully in cancer research and in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Shifting the Paradigm to Prevention

Prevention as a care paradigm is nothing new. As early as the 1940s, Mass General cardiologist Paul Dudley White, MD, proclaimed that the best way to lower heart disease risk was to practice preventive measures, such as exercise. Today, prevention is the bedrock of cardiac care, and a primary factor in the reduction of heart-disease-related deaths. Could the same approach work for Alzheimer’s disease?

“Evidence demonstrates that roughly 40% of age-related brain diseases, such as dementia, are attributable to modifiable risk factors and lifestyle,” says Jonathan Rosand, MD, MSc, co-founder of the McCance Center and J. P. Kistler Endowed Chair in Neurology.

Last fall, Dr. Rosand and his colleagues launched the Global Brain Care Coalition, an assembly of clinical, public health and research pioneers dedicated to promoting preventive care and lowering risk factors in diverse communities worldwide, with a goal to reduce age-related brain disease by 10% in the next decade.

“The brain health crisis is a pandemic, and we are bringing together a global community to address it,” Dr. Rosand says.

Learning From Nature

If nature is to blame for Alzheimer’s disease, it might also hold the key to staving it off. In 2019, Mass General neuropsychologist Yakeel Quiroz, PhD, and her colleagues in the Multicultural Alzheimer’s Prevention Program (MAPP) identified a woman in Colombia who carried a genetic mutation that all but guaranteed she would develop Alzheimer’s in her 40s. The woman, however, was 73 and only starting to show symptoms. Intrigued, Dr. Quiroz brought the woman to Mass General, where testing revealed she carried two copies of another, rarer mutation, known as APOE3 Christchurch.

“Everything pointed to that being the reason why she was protected, but we couldn’t be sure,” says Dr. Quiroz, Paul B. and Sandra M. Edgerley MGH Research Scholar 2020–2025.

Five years later, Dr. Quiroz and her team have the proof they need. The MAPP team has identified 27 members of the woman’s family who carry the same genetic predisposition to early-onset Alzheimer’s as well as a single copy of APOE3 Christchurch. That single copy of APOE3 Christchurch appears to have delayed the onset of symptoms by about five years — confirming the benefit seen in the original subject and suggesting it might be possible to mimic the same shielding effect through a drug.

“This extraordinary study illustrates how opening research to different cultures can advance our understanding of the disease and open new avenues for discovery,” Dr. Quiroz says.

To learn how you can help Mass General advance research in Alzheimer’s disease, contact us.