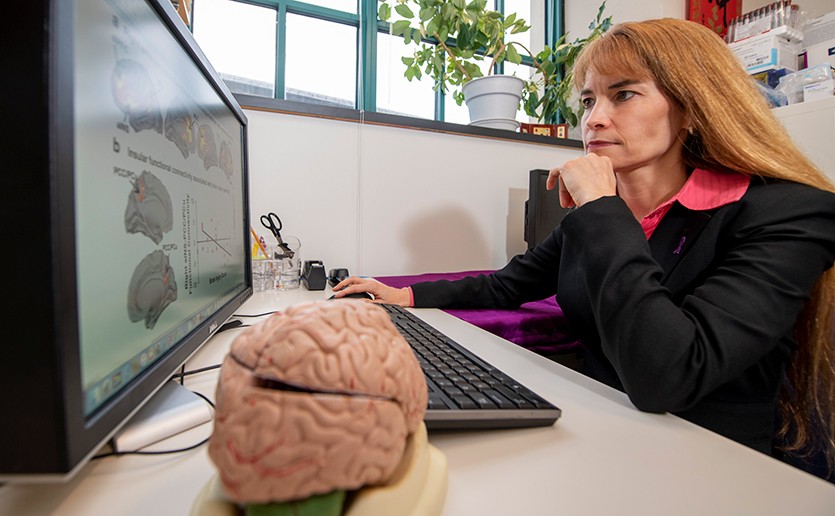

Eve Valera, PhD, is a psychologist and neuroscientist at Massachusetts General Hospital. When she speaks of her research on the connection between intimate partner violence and brain injuries suffered by women, it is with a certain violence of expression.

A mild traumatic brain injury, or TBI, is a concussion, typically associated with injuries to football players on the field or military personnel in the line of duty. “What people don’t think of are women being smashed in their heads by their partners on a regular basis,” Dr. Valera says. “Or thrown off porches. Or hit on the head with a baseball bat. Or having refrigerators thrown on them. Concussions behind closed doors are horrible things.”

“… As many as 33 percent of women worldwide experience intimate partner violence.”

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is “an invisible public health epidemic,” she states. In her lab at the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at Mass General, Dr. Valera uses a combination of careful interviewing, advanced imaging scans, and neuropsychological tests to identify abuse-related brain injuries and relate these injuries to cognitive and psychological functioning. Citing estimates that as many as 33 percent of women worldwide experience intimate partner violence, Dr. Valera contends large-scale, comprehensive studies are urgently needed and long overdue.

Intimate Partner Violence and TBIs

Dr. Valera first became interested in the topic when she volunteered at a domestic violence shelter during her time at the University of Illinois. A PhD candidate in clinical psychology, she was curious about the connection between partner abuse and women living with mild traumatic brain injuries. When she conducted a literature search, she was dumbfounded by what she found: absolutely nothing.

In response, Dr. Valera began to collect data that would become her published dissertation work. In a sample of 99 women, she found that 74 percent of them suffered at least one abuse-related TBI including brain injuries from strangulation; 51 percent sustained repetitive TBIs, many of whom sustained “too many to count.” Most did not seek medical treatment for and/or were not aware they had sustained what she describes as “IPV-related TBIs.”

“One of the reasons we know so little about partner violence is because it is an ugly topic. It’s very stigmatizing.”

Unlike a broken arm or punctured lung, these injuries are not immediately obvious. A range of behavioral, cognitive and psychological symptoms commonly reported after mild TBIs include headaches, nausea, forgetfulness, insomnia, poor concentration, dizziness, feeling depressed or anxious, and being irritable or easily angered. These symptoms can have negative effects on the ability to react and respond effectively — in essence, to get help and to get out of an abusive situation.

A First-of-its-Kind Study

The brain has two major hemispheres, and axons are nerve fibers that connect those two hemispheres as well as other regions of the brain. Cognitive impairments in TBI are thought to arise from damage to axons during a concussion that disconnects these brain networks. For Dr. Valera’s — and the world’s — first imaging study examining the effects of IPV-related brain injuries, she scanned the brains of 20 women abused by their partners.

Though the sample was small, the findings showed that the women’s injuries reflected abnormalities in functional neural network interactions associated with memory and learning. It was the first neuroimaging study to systematically examine and provide evidence of brain injury in women who had been physically abused by their partners. Dr. Valera has since published another neuroimaging study showing a relationship between structural connectivity and the brain injuries these women received from their partners.

“No one else has done this,” she says, “This is my passion.” Mass General is the ideal place to carry out her TBI research, Dr. Valera says, pointing to the Martinos Center and its state-of-the-art imaging capabilities, and Mass General Neuroscience, the interdisciplinary initiative which offers collaboration and shared knowledge. Mass General leadership has also been “highly supportive” of her work, she says, providing bridge funding until she received federal grants.

A loss of consciousness is not required, and, in fact, does not occur in most mild TBIs.

Raising Awareness, Reducing Stigma

An assistant professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School, Dr. Valera’s work extends beyond her lab in other ways too. She considers awareness building and information sharing significant parts of her job. “One of the reasons we know so little about partner violence is because it is an ugly topic,” she says. “It’s very stigmatizing.”

Dr. Valera gives lectures and presentations on TBIs and IPV to a range of audiences throughout the country and internationally, including judges and probation officers, and has become adept at explaining not only the science behind her brain research, but also the private suffering of women she hopes it will alleviate. She helps train police officers who are the first to respond to a domestic violence call and provides information to shelter directors. “Much of the general public doesn’t know what a concussion is,” she states.

All that is required for someone to sustain a TBI is what Dr. Valera calls an “alteration of consciousness” after some type of external trauma or force to the brain. A loss of consciousness is not required, and, in fact, does not occur in most mild TBIs.

Imaging studies are costly, at $625 an hour for a scan that may take 2.5 hours.

In football, she explains, spectators see the hit, which makes the injured player’s response — unsteady on the feet, slightly dazed — easy to understand. But a police officer responding to a domestic situation, who sees the same unsteady behaviors, but smells alcohol at the scene, may conclude that the unsteadiness is a result of inebriation. “Mild TBIs can mimic intoxication,” she notes. Her advice to police is to ask what happened. “If the answer is, ‘he slammed my head against the wall,’ entertain the idea that maybe a concussion just occurred.”

Women with undiagnosed TBIs may also face problems at shelters, when they are confronted with bright lights and excessive noise and a disruptive change in routine. They may be perceived as “uncooperative,” when they are really grappling with a brain injury.

Imaging studies are costly, she explains, at $625 an hour for a scan that may take 2.5 hours.

More Research and Funding Needed

Dr. Valera says that long-term studies are needed, with larger sample sizes and control groups. Recently, she was awarded what is the first federally funded large-scale grant to use neuroimaging to study the effects of TBI on women who have experienced IPV. She plans to study 144 women, all of whom have experienced IPV, but half with TBIs. She also wants to research the long-term impact of repetitive brain traumas, which she thinks, based on preliminary evidence, will likely include significant neurodegenerative changes. However, she will need additional funding to do that.

But the costs to women are incalculable. “Look around and talk about it in the open,” she advises. “It’s more common than people think.”

To learn more about how you can support the Mass General Department of Psychiatry, please contact us.