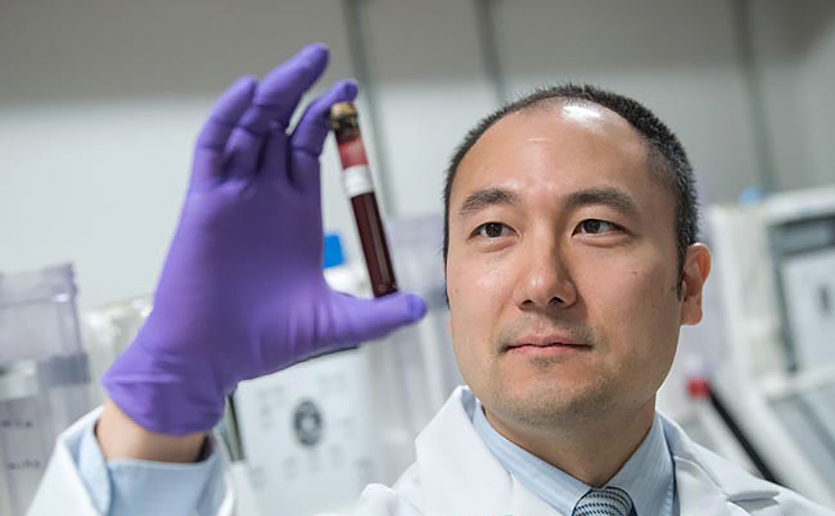

In his lab at the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, David Miyamoto, MD, PhD, holds a plastic disc up to the light. It looks like a DVD movie disc but with two tubes attached and a series of tiny channels embedded in it. This device holds great promise for early cancer detection using a technique called liquid biopsy.

“We remove the haystack and the needle left behind is the cancer cells.”

“It’s really a feat of engineering,” Dr. Miyamoto says, standing near a wall of whirring machines known as microfluidic processors as they circulate blood through channels on such discs.

Named the “CTC chip” after the circulating tumor cells (CTCs) which are its quarry, the device removes all normal red and white blood cells from a patient blood sample, leaving only tumor cells and other abnormal blood components behind. The word “chip” is a reference to an early version which resembled a business card-sized microchip.

Early Cancer Detection Tools

CTCs are hard to find but immensely useful in yielding clues about the presence and characteristics of cancer. The earlier a cancer is found, the more likely it can be successfully treated. Equally important, CTCs can help doctors monitor patients for cancer recurrence.

“It’s like finding a needle in a haystack,” Dr. Miyamoto says. “We remove the haystack and the needle left behind is the cancer cells.”

Dr. Miyamoto is a leader in a collaborative enterprise among physicians, bioengineers and molecular biologists at Mass General Cancer Center and beyond. He and other researchers are advancing cancer detection with liquid biopsy technologies — a new set of tools, including the CTC chip, that analyze blood or urine samples to diagnose cancer.

Liquid biopsy technologies seem poised to change the course of cancer diagnostics in a similar way to earlier cancer breakthroughs, such as the Pap test, which led to a dramatic decline in cervical cancer deaths after it was widely introduced in the 1960s. But while the Pap test screens only for cervical cancer, liquid biopsies can be used for many different types of cancer including liver, lung, prostate and others.

“These new technologies hold great promise because they will help us diagnose cancer sooner, with greater accuracy and at a stage when treatments can be most effective,” says Daniel Haber, MD, PhD, director of the Mass General Cancer Center.

Dr. Haber is a pioneer in the field. He and Mehmet Toner, PhD, a founding director of Mass General’s Institute for Bioengineering and Biotechnology, developed the CTC chip, a first-of-its kind device, in 2008.

Encouraging Collaboration

“There’s a lot of excitement here,” says Lecia Sequist, MD, MPH, director of the Center for Innovation in Early Cancer Detection (CIEDC) at Mass General Cancer Center. “A liquid biopsy or test is one of the easiest ways to monitor people. There are so many different options to look at in the blood, urine or even the breath that can tell us about cancer.”

The CIECD encourages collaboration and partnerships among Mass General Cancer Center patients, researchers, and technology entrepreneurs to drive forward the understanding of early cancer biology, Dr. Sequist says. The center works to support the development of innovative technologies and launch pilot trials leading to early cancer detection and better treatments for patients at Mass General and around the world.

Home of the largest hospital-based research program in the country, Mass General is well positioned to bring together the necessary combination of patients, physician-researchers and bioengineers who can make this work happen, she says, adding that “pairing patients with novel technologies is our hallmark.”

Clues to Early Cancer Detection

Liquid biopsies — usually a simple blood test — have several advantages over the traditional tumor biopsy which requires removing a piece of tissue from the suspected tumor, possibly causing pain, infection, other dangerous complications and, sometimes, unnecessary treatments. Using the most advanced molecular and genetic science combined with bioengineering, this multipronged effort is expanding on several fronts.

Researchers are hunting for different substances in the blood, urine or breath that provide clues to cancer known as molecular signatures, or biomarkers. They are using liquid biopsies to investigate substances including circulating tumor cells, DNA fragments (ctDNA), exosomes (packets of molecules given off by tumors) and proteins. These tests reap measurable information that can help identify cancer, guide treatment or, as some researchers hope, prevent cancer from occurring at all.

The CTC chip is one of the most promising advances in liquid biopsy technology. By circulating a patient’s blood through its tiny channels using a process developed in the field of microfluidics, the chip finds tumor cells and other substances that reveal information about cancer.

Researchers in several labs at Mass General have already demonstrated the CTC chip’s capacity to identify various forms of cancer and the pathologies that lead to them in small pilot studies. They have also developed the ability to monitor patients for cancer recurrence. But large-scale human trials involving hundreds of patients are needed before CTC chip analysis can be used to benefit patients. Philanthropic contributions are needed to move this research to the next level.

Diagnosis and Uncertainty

Dr. Miyamoto was a college sophomore when he learned the importance of early cancer detection. As a student at Harvard University, he watched with disbelief as his apparently healthy roommate fell ill and eventually died from bone cancer. He wondered whether earlier detection would have saved his friend’s life.

“That had a huge impact on me,” says Dr. Miyamoto, who, 20 years later, is a radiation oncologist leading a research lab.

Dr. Miyamoto works on prostate cancer, which is notoriously difficult to assess. A diagnosis of prostate cancer leaves many men in a state of uncertainty. Most prostate cancers grow so slowly that they pose little danger and require no treatment. But it’s hard to know which cancers are likely to grow. The standard test — for prostate specific antigen (PSA) — is often inaccurate or unspecific. As a result, many men undergo monitoring, including repeat prostate biopsies with accompanying pain and side effects.

Safer, Easier, Better

Dr. Miyamoto recalls a patient who developed a dangerous infection resulting from the prostate biopsy. No cancer was found. But the man had to be hospitalized for the systemic infection.

He is now working to develop a less invasive test to detect prostate cancer early and help guide treatment. “It would be great if we had a simple blood test that could tell us if a man has prostate cancer and if it is becoming more aggressive and needs treatment,” Dr. Miyamoto says.

His pilot studies have shown, among other things, that the cells gathered with the CTC chip can be analyzed to understand a patient’s prostate cancer and guide treatment, both for cancers that have spread and those that have not. Larger studies confirming these results are needed.

Unexpected Discoveries

David Ting, MD, studies liver and pancreatic cancers at Mass General Cancer Center. An MIT engineering graduate turned oncologist, Dr. Ting wants to do what cardiologists have done for heart disease — develop preventive treatments like the widely used cholesterol-lowering drugs that keep arteries clear and prevent serious cardiac conditions.

The surprises he is finding with the CTC chip make him optimistic.

“We were looking for tumor cells,” he says, “but we’re finding all these other cells we didn’t know would be there.” That’s big news, he says, because the damaged liver cells they are finding reveal conditions such as fatty liver disease and cirrhosis — precursors to cancer. Liver cancer, a common cause of death in Asia, is a growing concern in the United States where conditions such as obesity are contributing to its increase.

Prevention as a Goal

Using the CTC chip in small studies, he and colleagues have developed a test that can help determine whether a person has liver cancer or is likely to develop it. They can see the difference between a patient with chronic liver disease and one who already has cancer.

If larger studies confirm that the CTC chip can find biomarkers in the blood that show a patient is heading toward cancer, he says, drugs could be developed to reverse that process.

No single technology will provide all the answers, but with more and larger studies, Dr. Ting says liquid biopsies should open the door to exciting new options.

“My pie in the sky is not just early detection,” he says. “It’s prevention.”

To learn more about liquid biopsies and the CTC chip, or to support early cancer detection research, please contact us.