When cancer spreads to the brain — a common condition called brain metastasis — it is much harder to treat. It often interferes with brain functions like thinking, speech, movement and memory — the very core of who we are.

Studies show that one in ten cancer patients will develop a brain metastasis.

But thanks to new targeted therapies, patients are living longer with brain metastasis while physician-researchers are forging a new era of understanding and treatment at the Brain Metastasis Program at the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center.

The multidisciplinary clinic sees patients whose cancer first appeared in the breast, lung, skin, kidney, or colon, and has spread to the brain. At the clinic, a board composed of medical specialists from across the hospital meets to plan treatment for patients with brain metastasis. These patients often have extremely complex symptoms. Metastatic brain cancer is the most common form of brain cancer. Studies show that one in ten cancer patients will develop a brain metastasis.

Nationwide Leadership

At the same time, physicians at Mass General are collecting cancer tissue samples, analyzing them with today’s powerful new genetic tools and reaching a new level of understanding of how brain metastasis works. Their scientific findings have been so groundbreaking that Priscilla Brastianos, MD, director of the Brain Metastasis Program, has been named to lead a nationwide effort, supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). It will analyze patient tissue samples and run clinical trials to learn more about this little-researched area of cancer medicine. The Brain Metastasis Program has become a national hub for brain metastasis research.

“We hope this work will help patients live longer. We desperately need better treatments,” says Dr. Brastianos, whose work is inspired by her grandmother and mother, both of whom died young of metastatic breast cancer.

The Brain Metastasis Puzzle

Scientists think of metastatic brain cancer in terms of a tree trunk with branches. The primary tumor has been thought of as the trunk that sends out branches to other parts of the body like the brain.

But in a landmark 2015 study, Dr. Brastianos and colleagues found evidence that the primary tumor may not be the trunk.

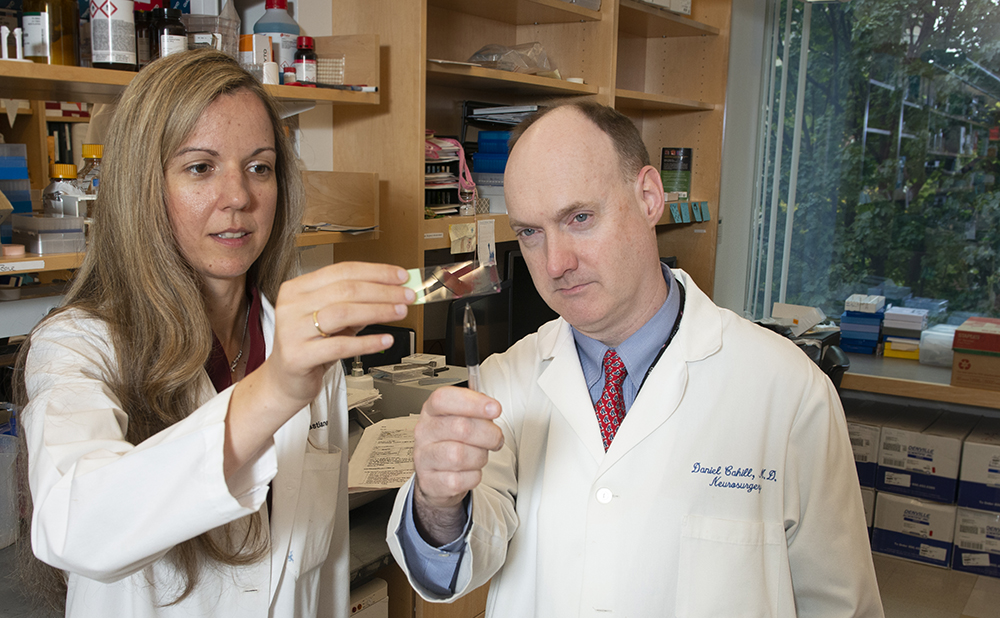

“Surprisingly, they’re separate branches of the tree,” says Daniel Cahill, MD, PhD, surgical director of the Brain Metastasis Program and surgeon in the Department of Neurosurgery, who has collaborated with Dr. Brastianos for years. The trunk is formed by genetic mutations in early cancer tissue, years before the primary tumor growth is even detected.

The Mass General Cancer Center is a leader in developing targeted cancer therapies.

Separate branches need different treatments because they each have different genetic alterations which can be targeted by different therapies. Targeted therapy is a form of personalized medicine in which a drug is chosen based on the specific genetic mutation or alteration found in a tumor’s cells.

These findings help explain why treating metastatic brain cancer with the same drug that treats the primary tumor often doesn’t work.

Using the Latest Genetic Tools

To do this work, Mass General scientists employ the latest genetic tools to analyze patient samples. Drs. Brastianos, Cahill and others compare the genetics of the primary cancer to the brain cancer in the same patient. They’re finding new and different genetic mutations and alterations in the brain cancer cells that may be treatable with specific drugs that target them.

The Mass General Cancer Center is a leader in developing targeted cancer therapies. Since 2004, when researchers identified a targeted therapy to treat a subset of non-small cell lung cancer, the program has been identifying new genetic targets and now has one of the leading programs running early phase clinical trials at the Henri and Belinda Termeer Center for Targeted Therapies.

Already, Dr. Brastianos and colleagues have identified new genetic targets in their patients’ metastatic brain tumors and have clinical trials underway using targeted drug therapies. They are also testing targeted therapies in laboratory models.

In the same way, the new national NCI funded trial that Dr. Brastianos is leading will collect and analyze patient samples from across the nation to identify genetic targets in metastatic brain tumors. Next, patients will receive targeted drugs to tackle the genetic mutations found in their tumor. The NCI study will focus on three specific mutations that tend to occur in brain metastases.

Where Philanthropy Makes a Difference

But there are more targets to be found and the physicians at the Brain Metastasis Program already have a large bank of 1,500 patient tissue samples that are waiting to be analyzed. Philanthropic dollars are needed.

• On the Hunt for Early Cancers

• Cancer Training Program Impacts Care in Africa

• Pioneer of Targeted Cancer Therapy Details Goals

“This is extremely expensive and high risk work,” Dr. Brastianos explains. It is high risk because metastatic brain cancer patients are usually in advanced stages of disease and are less likely to respond to treatment than patients in the early stages of cancer. The complexities of brain surgery add to the risk.

For these reasons, Dr. Cahill says, traditional funding sources are less likely to risk paying for studies of patients who are very ill. Philanthropy can help fill the gap.

Each day at the brain metastasis clinic, patients with complicated conditions are treated by specialists who meet to plan therapy and determine if a patient might benefit from a clinical trial or other treatments. They are also working to improve quality of life for their patients who may have deficits in brain functions like language, memory or movement.

With patients living longer, the program is busy coordinating surgeries, radiation, drug therapies and symptom management. Advanced genetic science is opening even more avenues for new treatment.

“We used to have to tell patients there was nothing we could do,” Dr. Cahill says. “But now we know there is a lot we can do.”

For more information about the Brain Metastasis Program or to make a donation, please contact us.