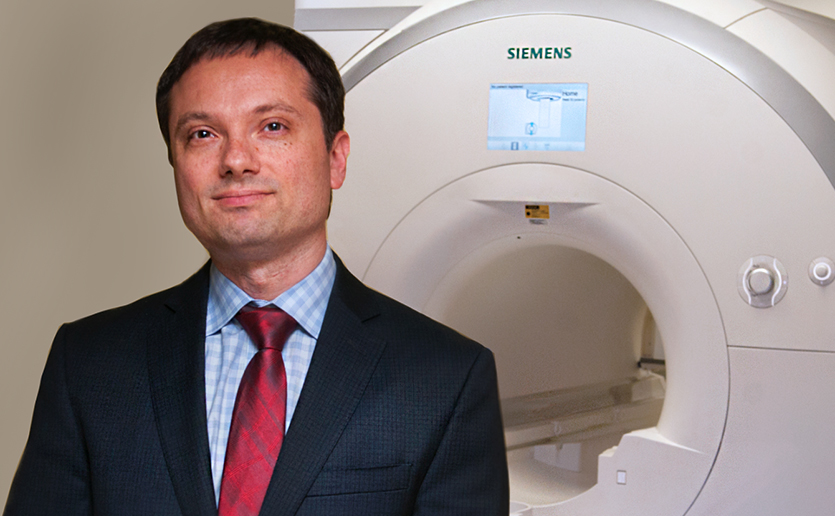

Psychiatrist and neuroscientist Joshua L. Roffman, MD, MMSc, aims to prevent psychiatric illness in children and teens through innovative brain research. His pioneering studies have shown the benefits of folic acid in both treatment and prevention of schizophrenia and normal brain development. Dr. Roffman is director of the Early Brain Initiative and co-director of Mass General Neuroscience, which brings together leaders in neurology, psychiatry and neurosurgery to create essential therapies for patients.

Why are you interested in brain health before birth?

In psychiatry, most known risk factors for mental illnesses are not “modifiable,” that is, they cannot be changed. In cardiology, for example, exercise, diet and quitting smoking are modifiable factors that can reduce the risk of heart disease.

To prevent mental illness, we need to discover “modifiable” factors. And these factors need to be harnessed before the disease begins to take hold in the brain, which for psychiatric conditions can be years before people develop symptoms. In fact, recent studies show that our best chance for meaningful intervention may be before birth. Much of my team’s work is centered around a new pregnancy and birth cohort study called Brain health Begins Before Birth or “B4.”

How will B4 shed light on the prenatal brain and mental illness?

We hope to discover protective factors that can reduce risk for mental illness. B4 will enroll at least 1,000 pregnant mothers and their babies and follow these children through at least the first few years of life.

Through survey data from each trimester, wearable devices that transmit data on stress, sleep, and body temperature, and electronic health record data, we will follow key risk-conferring prenatal elements such as maternal stress and infection, as well as potential mitigators of risk — such as prenatal vitamins, maternal exercise, sleep and nutrition.

The next step is to relate these to neurodevelopmental outcomes through annual pediatric assessments. We will also collect biological samples (DNA, cord blood, placenta) and conduct studies of “brain development in a dish” using cord blood cells.

Tell us more about the “brain development in a dish.”

Rakesh Karmacharya, MD, PhD, our team’s co-director for Translational Neuroscience, creates organoids — complex brain models made from patient-derived stem cells. We expose those organoids at various developmental time points to potential risk factors, like pro-inflammatory agents, and to potential protective factors like folic acid, shown to reduce the risk of autism and prevent spina bifida, a devastating neurological birth defect. This helps us determine whether different prenatal exposures might result in different brain development outcomes for the same children, a process we call “twinning.”

Why is collaboration such an important part of your work?

If we are successful, the interventions won’t necessarily show up in psychiatry — they will show up in primary care, women’s health, obstetrics, pediatrics. We want to take what we learn from clinical studies back into the lab and that requires translational neuroscience. Our team includes expert investigators in each of those areas, in a way that is uniquely possible at Mass General — where there is no “gap” between basic science and clinical studies.

If we are successful, the interventions won’t necessarily show up in psychiatry — they will show up in primary care. Women’s health. Obstetrics. Pediatrics.

How does philanthropy play a role in your research?

Our studies are ambitious and groundbreaking in ways that are hard to fund through federal sources. Philanthropy is essential for our studies to reach their full potential. We need support for studies of specialized populations — such as moms exposed to COVID-19, obstetric complications, or substance use early in pregnancy. Studies of families with increased genetic risk also have the potential for dramatic results.

In a previous study, when moms with an older child with autism took folic acid early in pregnancy, the younger sibling’s risk of developing autism was half of what it otherwise would have been. We want to know if the same is true for other prenatal interventions, across a range of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence as well as a diverse range of racial, ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Are you seeking participants to enroll in your studies?

Yes, absolutely. Our B4 cohort is enrolling pregnant women early as the first prenatal visit. Mass General is home to about 3,800 births every year, and ultimately, we would like to include as many of these families as we can. We are working with providers in obstetrics clinics throughout the Mass General system, who are helping enroll women around the time of their first prenatal appointment.

We are also actively enrolling participants in our ACEND (Assessing COVID-19 Effects on Neural Development) Study, with an emphasis on Latinx populations because of their higher rate of COVID-19 hospitalizations. The question we are asking is not just ‘What adverse effects might the pandemic have on developing brains?’ — but more importantly, ‘Of the kids who were exposed to COVID-19 and did well, what can we learn about these pregnancies that might suggest new protective interventions?’

To enroll in these studies, email B4study@mgh.harvard.edu.

To learn more about how you can support the study of the prenatal brain or to make a donation, contact us.